How the Parametric Press explains the environmental cost of digital consumption

Have you ever wondered how much carbon dioxide is released when you stream or download eBooks or videos? How about when you opened this article on your phone or computer? There are environmental costs when the packages purchased on Amazon are transported through warehouses and shipping centers to get to our homes. In a similar way, there are hidden environmental costs when we download eBooks that are transported from data centers and networks across the world to appear on our screens.

Global warming is happening, and its consequences are being felt around the world. The biggest question is how much the climate will change and what society should do. Parametric Press’ “The Climate Issue” considers this question as it tackles a range of topics. “The Hidden Costs of Digital Consumption,” explains how different types of media (websites, audio, video and data packets) produce different levels of emissions. The authors suggest that understanding how digital products and services work is an essential step towards addressing the impact it creates on the environment.

“It’s important to remember that ultimately creating videos, creating content like that by itself is not the problem, the problem really is the way we store it and the way we transmit it on the Internet,” said Shobhit Hathi, an Applied Scientist at Microsoft and one of the authors of “The Hidden Cost of Digital Consumption.”

Storybench spoke to Lilian Liang, Halden Lin, Aishwarya Nirmal and Shobhit Hathi––authors of “The Hidden Costs of Digital Consumption,” to understand how carbon emissions are also a result of loading digital information and to hold some of the companies accountable for environmental decision-making.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

How did you measure carbon emission and where did you collect the data from?

Aishwarya Nirmal: We computed a lower bound for emissions of each digital activity by using constants for the energy consumed in transmitting a byte of data (X) and the EPA’s US national weighted average for grams of CO2 emitted for energy consumed (Y).

We collected data on the number of bytes (n) that were transferred over a fixed period of time for each digital activity. We then plugged n into the following equation to compute emissions:

n bytes × X kwh/byte × Y g CO2/KwH

Your article discusses the hidden cost, but perhaps there are also hidden savings? In the sense that people can download a book instantly rather than going out to buy it in a store or have it delivered to their doorstep.

Lilian Liang: That’s an interesting way of framing it. Either way, to store information in any form, whether it’s like a book or whether it’s the internet, it will cost resources. For example, digitizing or archiving digitally can save more than printing a book which may or may not be true, but I guess we were more focused on breaking that [idea] that “tech is a purely clean industry.”

Halden Lin: With books and physical means of storing information, it’s very clear to us how environmentally impactful they are. When you move to tech and digitalization you kind of get lost in this fantasy land where you think that everything is perfect and clean. That’s the lens through which we were thinking about this article. It’s like you know that physical things are dirty, but when you move to tech, all of a sudden, everything’s clean. The reality is that it’s not. It might be cleaner, it’s true. But there’s a lot of stuff that’s hidden that you aren’t aware of and you probably should be aware of.

Another point discussed in your piece is the impact of streaming versus downloading content. Does your article imply that downloading is more environmentally friendly?

Halden Lin: I think that’s the implication. When you stream something you essentially download it over a period of time. I guess the advantage of streaming is let’s say you load a YouTube video, and you watch a minute of a 10-minute video. You might only stream. You might only end up actually downloading maybe two minutes of it. Whereas if you were to download the video, then you’d be obviously incurring the cost of the whole 10 minutes when you only actually use one minute of it. So, I guess it’s a tradeoff.

Shobhit Hathi: It definitely depends on the use case, but the difference in an individual person downloading or streaming is probably quite trivial and the gains you would see in terms of an environmental impact would probably be limited. The main environmental cost doesn’t come from a person actually streaming or downloading, it really comes from the infrastructure setup to support either one. One of the themes that we wanted to convey with our article is individual people are important and what your actions do matter, but ultimately the real environmental costs are actually incurred by these large infrastructural decisions rather than a case-by-case basis, like how much you should stream or what quality you should stream versus downloading.

Companies that offer offline content as a “premium” service effectively encourage the user to consume more energy to transmit data if one watches or listens to the same content multiple times. Any thoughts on that?

Aishwarya Nirmal: Yeah, there was one article that we found [that looked at] USA Today. In order to comply with [the European Union’s] General Data Protection Regulations in 2018, they had to remove a lot of ads from their website. That reduced the size of the data that needed to be transmitted to the website by a really significant amount. So, you could imagine that the website without ads would therefore have a lot fewer carbon emissions.

Shobhit Hathi: Companies are essentially encouraging consumers to be more data-heavy and actually incur higher environmental costs. I’m not a policymaker on this, but I don’t think that it’s like a conscious decision that companies want to incur higher environmental costs. It’s one of those hidden costs like every decision that we make in our digital and our normal lives has a cost and we push that cost onto things where it’s felt the least. Unfortunately, what we noticed from writing this article, we can intuitively sense in our daily biases that cost is usually put on the environment a lot of times. Incurring more carbon cost doesn’t directly hurt a company and it doesn’t directly hurt us right now. That’s why it’s such a hidden cost. I think that the business model you mentioned doesn’t encourage higher carbon emissions, [but]it definitely doesn’t mind them either. And I guess that’s the kind of sense I got from writing this article is that the cost is kind of just hidden and pushed out of sight.

Halden Lin: It’s just a byproduct of the money-making scheme that they have.

Who pays for this energy for digital consumption? Should consumers be aware of the environmental impact?

Shobhit Hathi: We kind of sketched out the pipeline for YouTube. It really depends on what point of the pipeline we’re talking about. If it’s the point of the pipeline where the data centers are, then the company running the data centers pays for it. If it’s transmitting over the internet, then the people that own the cell towers and the buyers pay for it. And then if it is through the Wi-Fi that you use or the device that you own, then you’re paying for it. This kind of monetary cost depends on what part of the pipeline we’re looking at. In terms of the environmental costs,I guess sadly [it is felt most by] the people that live in areas that suffer the most from climate change.

Newspapers like the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal are now focusing more on interactive articles. How much impact do these interactive articles have on the environment?

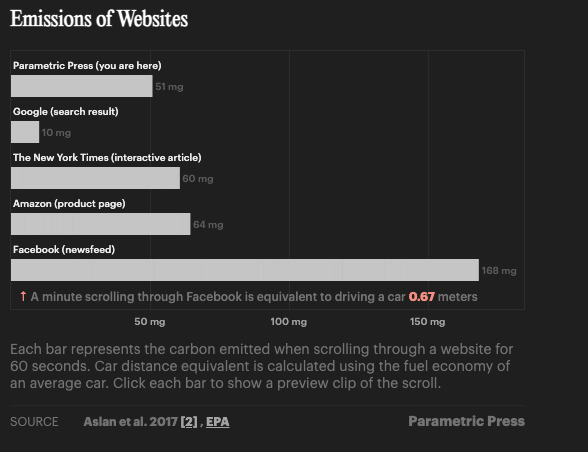

Halden Lin: That’s a great point. We kind of tried to play this tongue in cheek. If you look at the first chart on emissions for different websites, our own article is on the list. And I think we’re roughly comparable to how big a New York Times interactive article is. I think in the grand scheme of things, interactive articles are actually relatively light compared to videos or large photos with lots of media. I think it’s true that interactive articles tend to be heavier because of the data and maybe the media involved. I don’t know if there’s a great solution to that. I do think that in many cases interactive articles have the educational value that outweighs the environmental costs.

Lilian Liang: I think every decision we make will, unfortunately, have some kind of impact or some kind of carbon emission and certain actions will have slightly different costs. I think in the grand scheme of things from what we found, a majority of those costs still came from global infrastructure. For example, an interactive article might produce more CO2 because you have to load more elements, compared to a traditional text article.

Halden Lin: I think we could apply the same argument to a lot of the things we use on an everyday basis. Like, would we say let’s get rid of Netflix or video streaming because of the environmental impact? I think a lot of people just say, ‘We’d like our Netflix.’ We like our video streaming but let’s just make them more efficient. It’s like cars are useful but we can make cars that are more environmentally friendly. It’s not about getting rid of something that exists but making sure that we use it in a responsible way.

Shobhit Hathi: I think it’s really good to be thinking about ways that we can personally be more conscientious in how we consume data and how we create articles, but when we look at the graph, we see that this Parametric Press was a total of like 51 milligrams of carbon, but like an Amazon product page has 64 milligrams and our thing loaded a lot of pictures and other things. And even then, it was still smaller than just opening Amazon once and looking at one product. I think we should be selective in what we put out and how much we consume. But at the end of the day, we also need to recognize that an article does contribute a little bit to putting CO2 in the atmosphere. But what’s much more likely is that you probably consume more than that, like surfing on your phone or going to YouTube and all these other things that are so built-in. It kind of comes down to the work you’re doing — making an interactive article [outweighs the] trivial carbon cost of producing it compared to normal straightforward text journalism. Then I think it’s important to go through with it and make sure that it’s doing some good. In general, it doesn’t seem that the data visualization aspect is such a heavy contributor to the environmental costs compared to a lot of other things.

Journalists of today are gathering skills from data visualization to other digital-storytelling methods. In this case, do you guys suggest alternative methods for multimedia journalists?

Shobhit Hathi: I think that’s a really good point that ultimately, the reason why we’re in a climate crisis is not because we are doing things we don’t want. We want things to be more convenient. We want cars, we want planes, we want oil to consume. I mean, we don’t really want it, but we feel like we need it. In that sense, there is consumer-driven environmental damage and carbon costs that’s happening that applies to how we want multimedia and how we want video journalism, even though that might have a higher cost than text journalism.

It’s important to remember that creating videos, or creating content like that, is not the problem. The problem really is the way we store it and the way we transmit it on the internet. One of the papers we cite by Christ Priest and others, it basically had suggestions on how the entire YouTube pipeline could be more carbon efficient. Our personal preferences do contribute to some environmental costs, but the thing to remember is a lot of our personal preferences and what we want is shaped by the infrastructure that exists. And the little things that we want generally don’t contribute as much to this environmental damage as the large infrastructural decisions that are made by the pipeline. For example, consuming content on your phone was the most environmentally expensive or carbon expensive aspect of the YouTube pipeline. The study found that there were certain days that YouTube or cell companies could tweak how they send data over cell towers and that would actually contribute much less to climate change, [rather than] convincing everyone to just stop watching YouTube on their phones, which is kind of an impossible task. What I’m trying to say is we have preferences, and everyone has preferences. So rather than convincing everyone to change their preferences, it makes more sense to put that burden on the people who are delivering and catering to their preferences.

What suggestions do you have for newspaper companies? Many of these hidden costs are related to journalistic work. How do we make companies like the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal and many others aware about this issue?

Lilian Liang: It’s hard to know how much a media company itself can do because in the end they’re still tapping into the internet infrastructure, YouTube’s infrastructure. I think the ultimate decision still is in the hands of these platforms like YouTubeand how they decide to deliver the content and make the infrastructure more efficient.

Halden Lin: I think in a similar vein to that, the other companies with hosting services like Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud –– these platforms, which I’m sure pretty much every news media company uses to host their content, these all have different environmental footprints. I think I’d agree with Lilian that there’s probably not too much a single media company can do because they don’t own the infrastructure and infrastructure really is the cost. The best you can do in a system where money is the incentive is probably try to reward the platforms that are taking action to become more environmentally friendly and pressure them. Data centers are a huge source of environmental costs in their electricity usage, and some companies are pushing to make their data centers run on green energy that have zero missions. Actions like that can make a sizable difference if done correctly.

Shobhit Hathi: From a technical point of view, I think media companies don’t have a lot of power over the environmental impact of videos, but media companies are important in terms of disseminating information and holding some of these other companies accountable for bad environmental decision-making. In the last section of our article we point out that it’s only after media scrutiny that companies change their problematic behavior.

- How stuff.co.nz tells the tale of two pandemics in Auckland with an interactive timeline. - October 20, 2021

- How the Parametric Press explains the environmental cost of digital consumption - March 1, 2021

- How the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism is reporting on water access around the world - November 12, 2020