How journalists use the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory to report on environmental justice

In 1984, a Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, leaked 45 tons of toxic methyl isocyanate gas, killing thousands of people and injuring hundreds of thousands. A few months later, another Union Carbide plant in West Virginia released a mix of less toxic chemicals into the air that caused over 100 people to be treated for eye, throat, and lung irritation. These incidents catalyzed public concern over industrial chemical usage, and in response, the US Congress mandated facilities to inventory and report chemical releases to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on an annual basis.

Thirty-four years later, the EPA continues to publish the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), and every year journalists comb through it, looking for stories. A decade ago, National Public Radio used the TRI and other sources to report the series “Poisoned Places: Toxic Air, Neglected Communities.” More recently, these data showed up in a New York Times article about the fight against environmental injustice. Regional news outlets, like IndyStar and Denverite, periodically use the TRI to report on toxins going into their local environments.

We caught up with Mark Schleifstein, a journalist for the Times-Picayune and Nola.com in New Orleans, who has used the TRI in his reporting for over 30 years. Professor Christina Fuller, from Georgia State University School of Public Health, also chimed in about how the TRI has aided her academic research on air pollution. Then we spent some time digging through the TRI on our own to see what’s going on with toxic waste release in our home state, Massachusetts.

Schleifstein first used the TRI in the early 1990s, when the local media had just dubbed an 85-mile stretch along the banks of the Mississippi River “cancer alley” due to the prevalence of both cancer cases and petrochemical manufacturers. Schleifstein and his coworkers published lists of the top polluters and most common pollutants in Louisiana’s seven parishes, as the state calls its counties.

The focus that Schleifstein and others brought to toxic emissions paid off.

“It resulted in dramatic reductions across the board over the next 10 years,” Schleifstein said.

In some cases, administrators hadn’t been aware that their companies were emitting toxins in such large quantities until they read the articles. Whether they’d been aware of their companies’ practices or not, administrators didn’t like being associated with toxic pollution.

In October 2019, Schleifstein reported for ProPublica about how, after a period of improvement, “cancer alley” is again slipping into a quagmire of pollution.

“Tens of thousands of people, living cheek-by-jowl with belching plants along the Mississippi River, are exposed to toxic chemicals at rates that are among the highest in the United States, according to the Environmental Protection Agency,” the article reads.

Although the situation is dire, Louisiana’s governor has set up a task force to look into ways of reducing toxic emissions, so Schleifstein is hopeful that things will turn around, maybe partly due to his writing.

Schleifstein thinks the public would benefit if more journalists were familiar with the TRI, and he recommends that new users familiarize themselves with these data by using the guides, tutorials, and search tools that the EPA provides.

“It would be really great for lots of folks across the nation to be doing at least a top 10 list every year,” he said.

Even these simple lists of the top chemicals released and the heaviest polluters can be enough to catalyze change, he said.

Schleifstein also stressed that the TRI has some shortcomings.

First, the numbers are self-reported, which lets facilities avoid reporting certain chemical releases, if they so desire.

“We still get reports about emissions occurring at night when nobody’s looking,” he said.

Second, TRI data are at least a year old by the time they’re released. Administrators from the companies Schleifstein writes about sometimes claim that they’ve adjusted their chemical release since the data were collected.

Lastly, facilities may release extra toxins when they start up and shut down unexpectedly, like when an ice storm took Texas by surprise last winter. These aberrant emissions often aren’t tracked or reported.

Air pollution researcher Christina Fuller has used the TRI to show that low-income areas in the Atlanta region may be disproportionately exposed to toxins. She appreciates that the TRI provides locations of facilities, as well as listing the toxins they release. Fuller often works with data her lab collects using air monitors, and while these data provide a real-time view of the toxins people are breathing, they don’t provide much insight into where the toxins are coming from.

Ideally, Fuller would like to see another layer of subtlety added to the TRI. Currently, companies report how much of each chemical they’ve released as one lump sum for the whole year, but whether a chemical is released all at once or over a long period of time can make a big difference in the health risks posed to nearby communities.

Nonetheless, Fuller thinks the TRI provides a useful tool that journalists can use to investigate sources of pollution in their communities, and maybe even use as a starting point for narrowing in on case studies.

“When someone gets sick from asthma, or they develop cancer based on exposure to air pollution, that’s actually an individual’s life,” she said. “And we just don’t want to forget that.”

Lead in Massachusetts as a proof of principle

We took Schleifstein and Fuller’s advice and looked at what was going on with toxic chemical release in Massachusetts in 2019 — the most recent year for which the TRI is available.

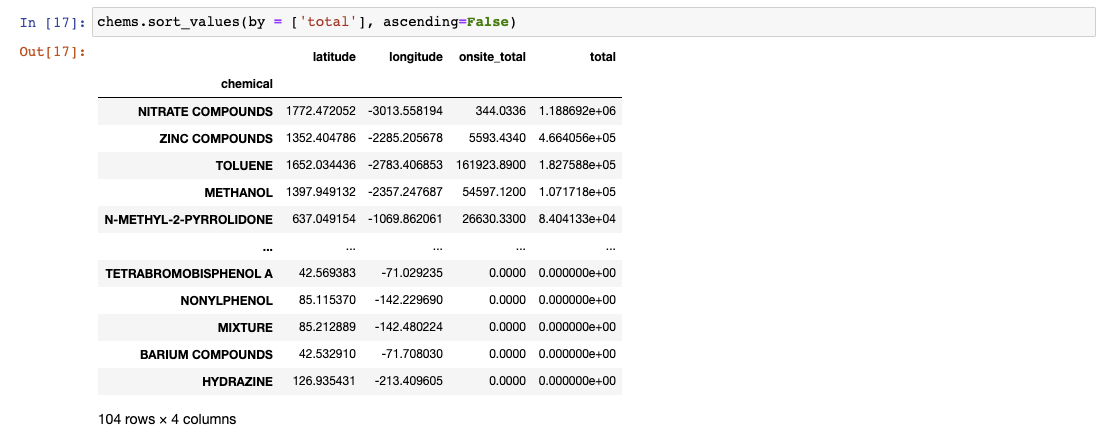

The top 10 chemicals released in Massachusetts in 2019 were: nitrate compounds, zinc compounds, toluene, methanol, lead compounds, N-Methyl-2-Pyrrolidone, butyraldehyde, chromium compounds, nitric acid, and ammonia. Although all of these chemicals can be dangerous under certain circumstances, the EPA has designated lead as a chemical of particular concern because it accumulates in the human body, eventually causing neurological damage, and repeated exposure can be as harmful as a single large dose.

Manipulating TRI data using Python in Jupyter Notebook

The two facilities that released the most lead in Massachusetts in 2019 were the polymer and glass technology company Incom Inc in Charlton, which released just over 44,000 pounds, and the waste disposal company Clean Harbors of Braintree, Inc, which released just over 22,000 pounds. Both release most of their lead in disposal sites, away from their primary locations, and together they account for two thirds of the lead released in Massachusetts.

The third facility on the list is the U.S. Army Garrison at Fort Devens, clocking in at nearly 11,000 pounds, or around 10% of the state’s lead release, mostly due to the amount of bullets fired on the base’s shooting ranges, according to a spokesperson for the base. The firing ranges are used for military training as well as FBI and local law enforcement, they said.

While trained law enforcement officials may keep the streets safe, lead from bullets quickly leaches into soil and can poison people and wildlife. Adults may only exhibit minor symptoms such as abdominal pain and headaches upon lead exposure, but children are more sensitive, and can contract permanent neurological damage.

The weapons manufacturers Smith&Wesson and Savage Arms also reported releasing 5,455 pounds and 2,801 pounds of lead into the environment, respectively. Together with the firing ranges at Fort Devens, these facilities contribute 18% of the lead that’s going into the environment in Massachusetts.