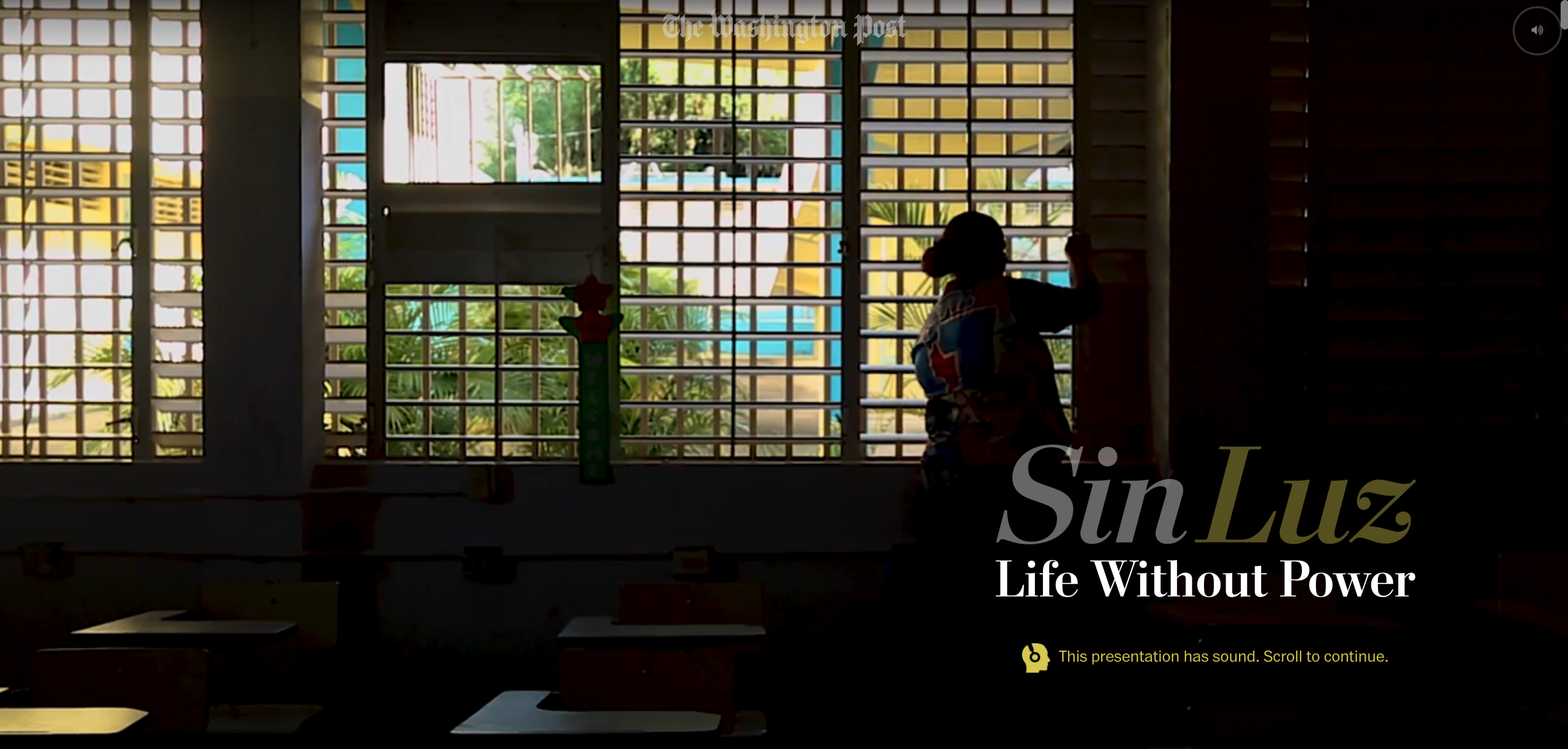

How The Washington Post covered the largest blackout in U.S. history

When Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico in the fall of 2017, locals knew there would be a recovery process. As a high-end Category 4 storm, Maria dumped feet of rain onto the island and blasted it with winds reaching speeds as high as 118 miles per hour. But the aftermath turned out to be far worse than imagined. Electricity grids were knocked out across the territory, and thanks to a combination of poor governmental response and shaky infrastructure, it took nearly a year to restore a power. Even nine months after the storm, thousands were still relying on antiquated generators for electricity.

The Washington Post had reporters stationed on the ground as soon as the storm hit and it didn’t take long to find out that the power outage would be a massive story of its own. So after doing their initial coverage, The Post assembled a trio of journalists and sent them back to Puerto Rico, this time to catalogue the devastating reality that life without electricity poses. The product was “Sin Luz,” an award-winning multimedia piece telling the stories of those on the front line. Storybench caught up with Arelis Hernández, one of the reporters on the team, to learn how they captured the struggle and strength of the Puerto Ricans.

What was the origin of this story? Obviously, you didn’t need a tip line to know about the disaster in Puerto Rico, but how did this story get going?

I would say it was a group idea. I had been reporting in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of the hurricane, as had other colleagues of mine, and we realized, “Hey this power situation looks like it could go on for a long time.” So the idea was there, but we just didn’t have the tools to execute the story yet. Once we all got back [to D.C.], we sat down and talked it through with some editors and decided to return to Puerto Rico.

How long were you in Puerto Rico?

I spent four months out of this past year in Puerto Rico, but reporting for “Sin Luz” took a week.

This story is broadly about Puerto Rico, but it’s told through the stories of the towns of Yabucoa and Utuado. How did you settle on those as entry points for the story?

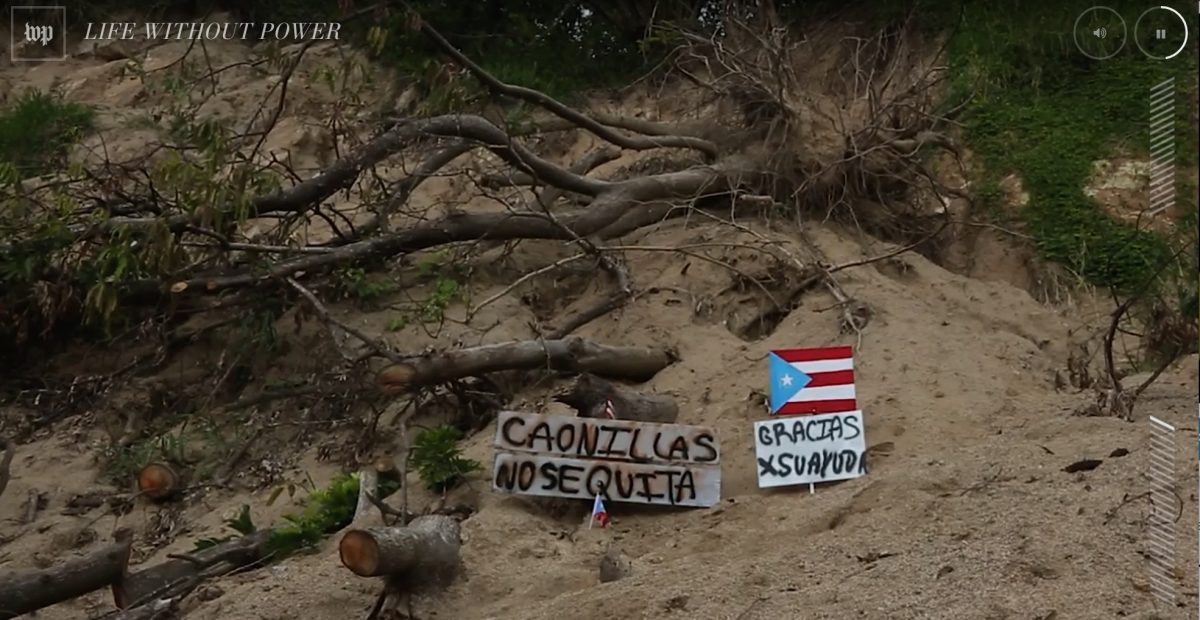

Yabucoa and Utuado were severely damaged and really, really hard hit. Yabucoa came up as a location to focus on because I had actually met the mayor during my prior reporting, during all the chaos after the storm. He had given me a really raw rundown of what was happening in a way that people just weren’t at the time, really being honest in a way that the state government wasn’t. So that was one part of it.

For Utuado, we did a story about a church there after the hurricane during our immediate coverage, and through that we met this family that kind of served as keepers of the church in Utuado. They were really well known and knew everyone, so they sort of ended up being our connectors in Utuado. They helped us find a lot of amazing people and stories.

How did you go about finding these individual stories? For example, there was a video explaining how a kid designed a zip line basket to get across the river. How do you find people like that?

For one, we had been there months earlier, so we had seen the terrain and knew that they would be cut off by this river. But this family in particular had been featured on the local news, so we knew of them that way too. Luckily, the Ortiz family [from the Utuado church] had their contact information, so we could find them that way.

This story must have been very hard to report on from an emotional perspective. Was it hard to separate your feelings about what has happened to Puerto Rico from your reporting? Was it even necessary to create that separation?

I don’t think you need to. It’s what makes it powerful. I’m a human being and I happen to be Puerto Rican, so while I obviously couldn’t understand their suffering in the same way, I was tangentially experiencing their desperation.

Journalism isn’t perfect, I would have preferred that these folks write their own stories. But with me being the conduit, and embodying their emotions, I can try and be the next best thing and relay what they’re feeling.

On a really basic level, the lack of electricity and infrastructure seems like it might hinder your ability to do the reporting, especially since you were lugging around cameras and laptops. Did you run into trouble with that?

[Laughs] Oh, definitely! That was part of the terrain. When we went down there, cell reception was incredibly difficult and access to electricity was difficult, which is why so much of the post-production had to wait until we got back. It was challenging, there were times where we had to pull off the side of the highway all of a sudden because we got a flash of cell reception. We would stop, park, and hold the phone up so we could send something back to D.C. Basically, we were like the rest of the Puerto Ricans.

That also meant that for “Sin Luz,” our reporting was just gathering, basically. There weren’t hard deadlines, we just had to get as much as we could.

You worked with two other video journalists on this. Did each of you specialize in a certain aspect of this and come together?

“It was basically five weeks of sitting in a video pod with them when we got back.”

It was very much a joint project. I was blessed and honored to work with them, we were basically in symbiosis the whole time. We understood what we were trying to accomplish, and they were super deferential to me in cultural matters since I am Puerto Rican. I sat down with them through every edit, every interview, helping with translating, picking out certain things…it was basically five weeks of sitting in a video pod with them when we got back. We still had to work on our respective parts, of course. I was the “writer” of the group, so I took care of the text, but it was really a collaborative process.

And just to clarify, we had three people on the byline, but there was a total of 18 journalists working on this, from editors to drone operators. We were meeting at 10 a.m. every day back in D.C. going over every detail.

How did you determine which parts should be video interviews, which should be text, that sort of thing?

That honestly came up later. When we were in Puerto Rico, we were pretty singularly focused on video and interviews. Those 10 a.m. meetings back in D.C. are really where we fleshed out the graphics and order of everything. In fact, the order of this story changed several times before we got to a place where it felt cohesive. It took a lot of time to get that squared, because even though we were using a template that the Post had used in the past, we really wanted to go even further with it. Luckily for those of us who went to Puerto Rico, we also had our fabulous engineers and developers thinking ahead and playing with models and graphics before we even got back.

What you really notice while watching and reading the piece is that it forces you to slow down. Was that a deliberate choice to pace the story like that?

“It reached a million views, and the average length of visit was eight to ten minutes.”

That was actually a huge anxiety of ours. We were like, “Oh my god, it’s too long. No one is going to have the time to engage with this.” We were really looking for ways to cut and make things as succinct as possible. But after a while, we stopped and thought “You know what? Maybe we don’t want people rushing through this.”

I still think it’s too long sometimes, but the numbers have been impressive. It reached a million views, and the average length of visit was eight to ten minutes. Yeah, we were really surprised by that. Although those were the numbers back around when it came out, so I’ll have to go back and double-check that.

Is there anything else notable about the article or the process that I didn’t ask about?

In terms of the narrative structure, we had a significant debate. For me, it was really important that we held up the dignity [of the Puerto Ricans]. I really didn’t want to just show them as victims, and that’s a really easy thing to do. So many stories are just, “Look at all these poor people.”

That wasn’t the story we wanted to tell. We saw a lot of resilience, and paying homage to that was really important. We wanted to get intimate with these folks, provoke something within the viewer. And now, even with traveling to awards ceremonies for this, what means the most to me are the people who come up to me and say they broke down and cried while watching this. That, to me, is more important than anything.