Could the “science of content” help reveal why stories go viral?

Digital media companies like BuzzFeed and even legacy newsrooms such as The Washington Post are constantly talking about how their operations have become increasingly data-driven. But despite the immense amount of data being generated on – and collected from – social media platforms, engagement editors, marketing specialists and digital media gurus are far from understanding the exact reasons a story goes viral.

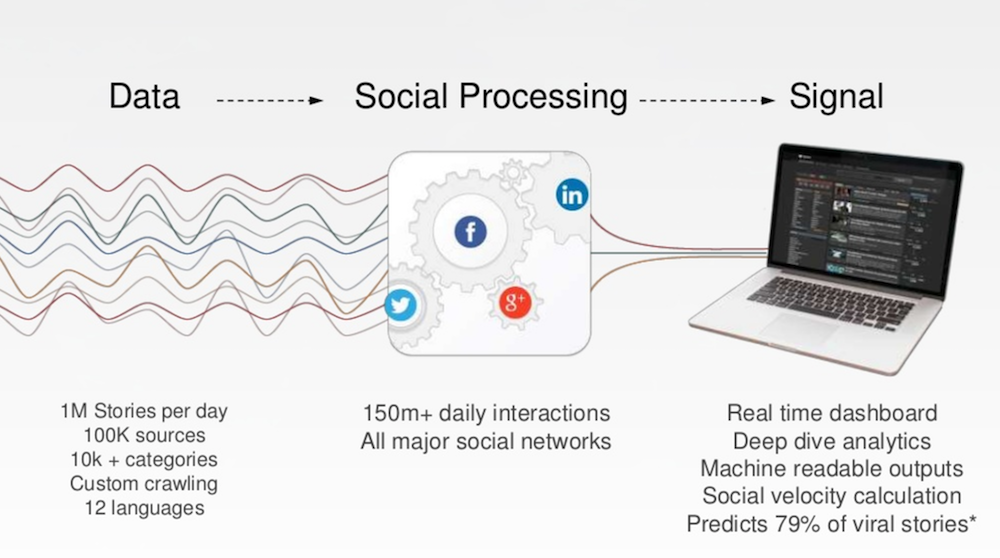

Paul Quigley, CEO and co-founder of the social media monitoring firm NewsWhip, thinks the answer lies in what he calls the “science of content.” Speaking earlier this month at WhipSmart, a conference on social media and digital strategies convened by his company, Quigley said that after centuries of trying empirically to understand why stories spread, journalists and content creators are now on the verge of getting answers.

“We never really had evidence before about why some stories work and others do not,” said Quigley. “Now, we can analyze social data and see the patterns. Successful stories are built on analytics.”

Predicting engagement

Analytics-based strategies are a recent phenomenon in the world of storytelling and NewsWhip is far from the only company deriving insights from data for publishers. From Chartbeat to CrowdTangle, there are dozens of companies offering services and software focused on monitoring social platforms to measure what goes viral. Some news organizations, like The New York Times, employ data scientists to find out how best to leverage data on their readers. But by employing the latest methods from data science, Quigley believes, companies like NewsWhip may be able to figure out why stories go viral.

Of course, data-driven newsrooms have been applying the concepts of data science for years.

“The more you publish, the more opportunities you have to look at things that are happening, read comments, have a new hypothesis, test a hypothesis,” BuzzFeed publisher Dao Nguyen told Fast Company last year. “You can begin to form ideas about content,” she said, “how it should be made, how it should be presented, and where it should be distributed and whether or not that has an effect.”

Quigley agrees. At WhipSmart, he told attendees that “we can now analyze social data and see the patterns” and that data will help answer basic but fundamental mysteries surrounding content creation and distribution. Which stories and topics reporters should cover, for example, or what formats newsrooms should employ, he said. Or what devices should become priorities and what networks companies should be on. Those are some of the questions the billions of data points will allow publishers to answer.

Over the next five years, Quigley said, the world will see the rise of the “science of content” in newsrooms and other creative industries.

The “art” to crafting stories

Quigley believes that despite all the data science, there’s still an “art” to crafting successful stories. The journalists and storytellers who will be most successful in the coming decades will be those that can best determine the components, angles and elements of a story that make it most effective. That will become increasingly important as publishers compete over audience attention.

“We cannot buy attention anymore,” said Quigley. “We have to earn it. And we will do that by creating content people will want to engage with, subscribe to, pay for.” He also highlighted the rise of ad-blockers as another sign of the need to acquire consumers’ attention with effective content.

That’s inline with what BuzzFeed founder Jonah Peretti believes. “Having technology, data science, and being able to know how to manage, optimize, and coordinate your publishing is the thing that gives you a competitive advantage,” Peretti recently told Fast Company.

At WhipSmart, Ashish Patel, the publisher of digital news company NowThis Media, pointed to a specific example of how data from social media informed their news strategy. After seeing that some NowThis videos had low viewer retention metrics, his team looking into the analytics to find out why. They found that 85 percent of the audience was accessing those videos on mobile devices. So, they took their smartphones out and started scrolling down their own timelines to understand what the problem could be. “There was no sound,” Patel said. “The solution we found was to use big text on screen and remove talking heads. You have to think about your audience and what they are doing on the other end.”

The big tension

In a world where data and analytics will drive decisions inside newsrooms, a very human tension remains, Quigley said. Newsrooms will have to deal with situations where data points to something that goes against “the integrity or principles of the brand.” That’s when human editorial judgment will need to come in.

To Youyoung Lee, director of audience development at Vice, that presents an opportunity for publishers to find new audiences. During one of the WhipSmart panels, Lee hinted at how that conflict actually helped the newsroom find focus. “Data helps inform a lot of the choices around what the audience is engaging with,” she said. “But more important than that is the storytelling we can do within those areas. The moment we start getting readers on the page that aren’t typical Vice readers, we see the engagement levels drop.”

That, it turns out, is an opportunity to explore ways to connect with those new readers.

Photo: NewsWhip.

- SXSW: ‘Excel is okay’ and other tweet-size insights for data journalists and news nerds - March 17, 2018

- NICAR: Data stories from last year that you could be doing in your newsroom - March 13, 2018

- How to scrape Reddit with Python - March 12, 2018